The end of Roe killed a young, vibrant mother—and likely many more

Say Her Name

In a bustling hallway on the sixth floor of a downtown courthouse, Alcira Ayala sat on a bench with her husband and daughter, anxiously waiting for her eviction case to be called. She held a black cloth bag filled with neatly organized records that she hoped would help her win her case and stay in the apartment that she and her family have lived in for nearly two decades.

Since learning this summer that her landlord wanted to evict them, Ayala had spent days calling and showing up at the offices of local nonprofit groups to ask for help.

She had hoped to get a free lawyer, but quickly learned that there aren’t enough in the city to represent everyone who needs help. To try to defend herself, she went to the L.A. Law Library to ask for guidance filing the legally required response to the notice. Then, she attended hours of online training hosted by the nonprofit Eviction Defense Network, which teaches tenants without lawyers how to prepare for court.

Read the rest on LA Times

You are living through the worst execution spree in three decades

Less Of This

This week is shaping up to be a very bad one for death penalty opponents in the United States. If all goes according to plan, states will put five people to death in a one-week span ending Thursday. That is an unusual, though not unprecedented, number of executions in such a short period of time.

To understand just how unusual it is, consider that in 2023, the total number of executions for the entire year was 24, less than one execution every other week. In 2022, 18 people were put to death, for a rate of roughly one execution every third week.

Indeed, one would have to go back almost three decades, to 1997, to find a parallel to what may unfold this week. During a seven-day period in May that year, Texas executed five people.

Read the rest on Slate

Defense lawyers worry that SCOTUS is about to overturn a death penalty precedent

Speaking Of...

On a March evening last year, death penalty lawyers, scholars and trained investigators gathered in an Atlanta hotel room to celebrate Wiggins v. Smith. The 20-year-old Supreme Court decision declared that defense lawyers in death penalty cases must thoroughly investigate the lives of those facing execution for evidence that might see them spared.

The court held that lawyers needed to explore a defendant’s medical, educational, family and social histories, as well as religious and cultural influences, and any prior time spent behind bars. Defendants whose lawyers failed to do so, the court ruled, could rightly claim they were victims of inadequate counsel, deprived of a basic constitutional right.

Read the rest on The Marshall Project

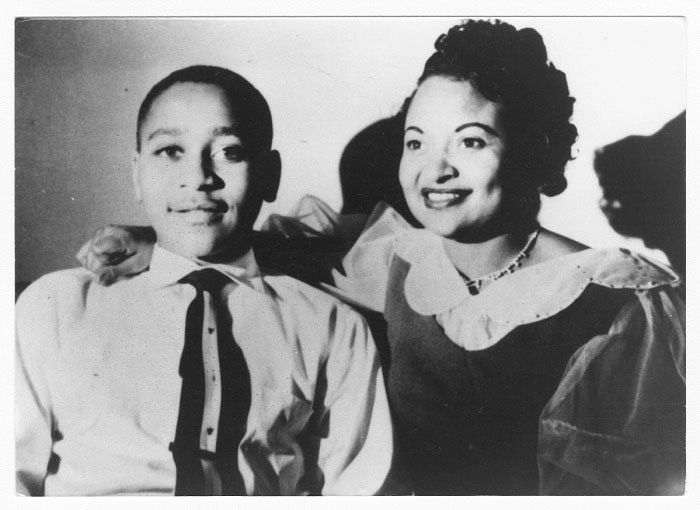

The true history of Emmitt Till and the civil rights movement

Say It Louder

Most everyone is taught that Emmett Till whistled at a white woman at a rural grocery store on an August Wednesday in 1955. The following Saturday night, that woman’s husband and brothers kidnapped, tortured and killed the 14-year-old boy in a barn in the Mississippi Delta. It’s an often told story, by history teachers and terrified parents, familiar for the tension between the gruesome details, like how his body was dragged down into the Tallahatchie River by the weight of a gin fan wrapped around his neck with barbed wire, and how Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket funeral, so the whole world could see what Mississippi did to her son.

What almost nobody knows, including me when I started reporting The Barn, my new book on the untold history of this famous murder, is that he allegedly whistled the day after a long gubernatorial election dominated by intense racial rhetoric. Mississippi during the election of 1955 was a place trapped in a cycle of hysteria, conspiracy and rage. “A Nazi rally,” is how former Gov. William Winter once described to me the state’s mood during the civil rights era.

Read the rest on Politico