The story of the openly gay leader of the civil rights movement

Watch This

This Pride Month, as part of our “Hidden Histories” series, we look at the contributions of Bayard Rustin, one of the driving forces of the civil rights movement, whose life as an openly gay man relegated him to behind-the-scenes roles much of the time.

Watch on PBS

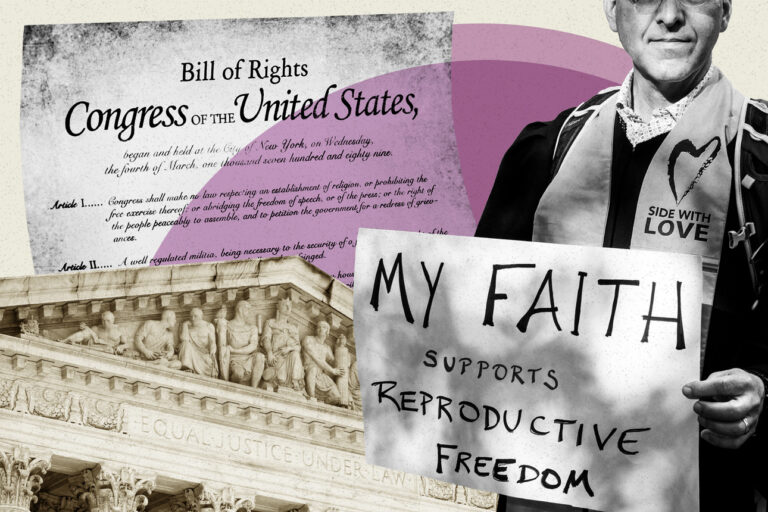

Progressive lawyers team up with Jewish leaders to win back abortion rights

More of This

Revs. Jan Barnes and Krista Taves have logged hundreds of hours standing outside abortion clinics across Missouri and Illinois, going back to the mid-1980s. But unlike other clergy members around the country, they never pleaded with patients to turn back.

The sight of the two women in clerical collars holding up messages of love and support for people terminating a pregnancy “so infuriated the anti-abortion protesters that they would heap abuse on us and it drew the abuse away from the women,” recalled Taves, a minister at Eliot Unitarian Chapel in Kirkwood, Missouri, as she sat on a couch at Barnes’ stately church in this quiet suburb of St. Louis.

“I thought: ‘Whoa, these people really are not messing around.’ But then I thought, ‘Well, I’m not messing around either.’”

So when Missouri’s abortion ban took effect after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last year, Barnes and Taves decided to fight back.

Read the story on Politico

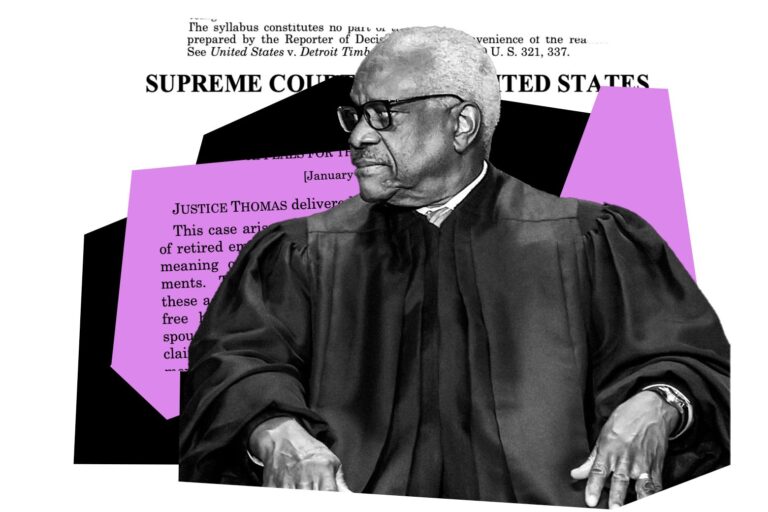

An aggressive Supreme Court is reshaping our lives

Less Of This

The Supreme Court, in the midst of a run of decisions that have stress-tested the core principles of US democracy, has rarely been so aggressive in using its powers — or been viewed with more skepticism by Americans.

With its 6-3 conservative majority, the court has issued a series of recent decisions enhancing its own role, in many cases by overriding regulatory agencies, the White House, Congress and state and local governments. Rulings have curtailed environmental protections, restricted efforts to regulate firearms and limited public-health initiatives. The court is set to decide on university affirmative action, student-loan relief and the rules for federal elections before the scheduled end of its term next week.

Read the story on Bloomberg

State Bar wants to disbar lawyer who tried to overturn 2020 election

Speaking Of...

Leah Litman teaches law at the University of Michigan Law School.

Many people watching Supreme Court opinions on Thursday may have breathed a sigh of relief as the court did not hand down any of the most-watched remaining cases (like the challenge to the president’s student debt relief program, or the challenge to affirmative action, or the challenge to LGBTQ equality and nondiscrimination protections).

But that’s only because a lot of people may have not been following the slow-motion disaster that has been unfolding in one of the less followed cases, Jones v. Hendrix. Jones involves a highly technical sounding, but practically significant, issue about when federal courts may correct wrongful convictions and wrongful sentences.

Essentially the case involves this scenario: What if it turns out that the federal courts that heard your criminal case made a mistake? And as a result of the courts’ mistake, you were convicted of something that isn’t actually a crime at all (because federal law doesn’t prohibit what you did), or, as a result of the courts’ mistake, you were sentenced to more time in prison than the law says you can be sentenced to? Can a federal court later correct the error in a federal habeas corpus proceeding when you challenge your conviction or sentence?

Today, the court, in a 6–3 opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas, answered that question with a no.

Read the story on Slate