Diverse judges are finally here, and they may be key to staving off the demise of democracy

More of This

President Joe Biden announced Wednesday his 11th round of judicial nominees, a diverse group of prospective federal judges that brings his total number of nominees to 73 — one more than President Donald Trump nominated during his first year in office.

The rapid pace of Biden’s nominations illustrates the weight Democratshave placed on countering Trump and Senate Republicans’ historically rapid — and markedly awful — reshaping of the federal bench over the last five years.

Biden’s nominees have been a departure from Trump’s fixation with choosing ultraconservative white guys to fill lifetime judgeships. Among the list are several people who will make history if confirmed, including the first Native American federal judge in California and the first openly LGBTQ federal judge in Wisconsin.

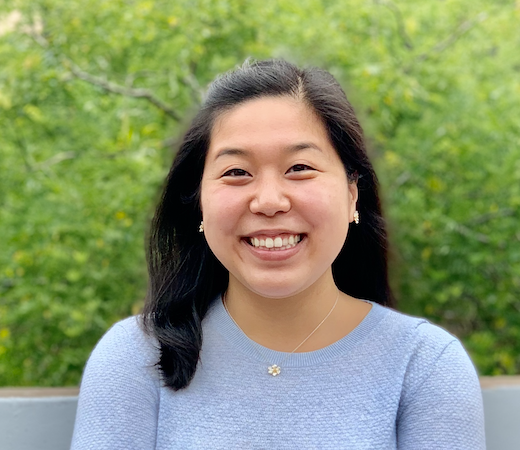

The latest round of nominees followed Monday’s Senate confirmation of Lucy Koh, the first Korean American woman to serve on a federal appeals court.

We can’t be sure exactly how these nominees will rule, but we know their diversity is a necessary counterweight to the revanchist conservatism Trump’s majorly white, mostly male judges were installed to enforce. More than a quarter of active federal judges were Trump appointees, according to a Pew Research Center study in January. Many of those judges have already issued rulings striking down gun safety measures, voting rights, abortion rights and more.

Read the story on MSNBC

The most dangerous conservative judges are not on the Supreme Court

Less of This

Republican-appointed justices on the Supreme Court have been aggressively pushing the legal system to the right for some time — and now seem poised to take even bolder steps, most notably reversing or severely weakening Roe v. Wade. The willingness of those now-six justices to align themselves so tightly with Republican Party political goals is hugely important, because the Supreme Court determines national law and creates precedents that lower courts must follow. That said, the high court issues relatively few rulings each year. Most issues get resolved in state-level courts or at the federal district or circuit court level.

Recognizing the importance of those lower courts, Republican officials and groups have long pushed to make them as conservative as they can, similar to GOP efforts to shape the Supreme Court. President Donald Trump in particular prioritized picking people who were deeply ideological and committed to GOP goals. Republican governors are now stacking courts at the state level with people aligned with the Federalist Society, the conservative organization that has played such a big role in moving the judiciary to the right at the federal level. “Republican governors have been very focused on getting conservative judges in place,” said Billy Corriher, founder of a newsletter called The Supreme Courts that focuses on high courts at the state level.

All of that work by Republicans to shape the legal system is paying off. These lower-level judges have effectively become a Republican super-legislature, blunting the policies of Democratic mayors, governors and presidents while largely upholding the moves of Republican officials.

Read the story on Washington Post

The Supreme Court won’t save us from police brutality, but state courts can

Speaking Of...

Erwin Chemerinsky is the dean of the School of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of “Presumed Guilty: How the Supreme Court Empowered the Police and Subverted Civil Rights.”

After the tragic killing of George Floyd, protests against police violence emerged in all 50 states. These conspicuous calls for change contributed to a sense that finally, the country’s leaders would take action to rein in police violence, which disproportionately affects people of color.

It should be the responsibility of the Supreme Court to enforce the Constitution and constrain the police. Several provisions of the Constitution — such as those in the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Amendments — exist to limit what the police can do. But throughout American history, and especially since the end of the Warren court, the justices have sided overwhelmingly with the police, narrowing the rights of criminal suspects and defendants.

As recently as October, the Supreme Court sided with the police yet again when it threw out two lawsuits against police officers accused of using excessive force, ruling that the officers were protected by qualified immunity. The court’s conservative majority is likely to remain for many years to come, and that fact brings with it another: Meaningful police oversight will need to come from the political process, from Congress and from state and local governments, rather than from the Supreme Court.

Congress certainly could act to improve policing. The proposed George Floyd Justice in Policing Act — by restricting the use of chokeholds by officers, easing the process of convicting police officers of misconduct and changing the rules around qualified immunity, a practice that makes it difficult to sue police — would make important and much needed changes. The Act has passed the House of Representatives, but it seems permanently stalled in the Senate.

This means, at least for now, that protections against the police must come from state and local governments. At the state level, courts can interpret state constitutions to protect more rights than those that the Supreme Court has found under the U.S. Constitution. For example, the Supreme Court concluded that because people have no reasonable expectation of privacy with regard to their discarded trash, the police do not need a warrant to search a person’s garbage. But in interpreting their state constitutions, some state courts have come to the opposite conclusion, requiring a warrant for such police searches. Where the Supreme Court has said that police officers who, in effect, use a traffic violation as a pretext to justify the search of a car are not violating the Fourth Amendment, some state courts have said that such an act violates their constitutions.

Read the story on NY Times

Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat in 1955. She’s still fighting for justice.

More of This

Laurence H. Tribe is the Carl M. Loeb University Professor Emeritus of Constitutional Law at Harvard University. Jonathan M. Metzl directs the Department of Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University. David Hogg is a founder of March For Our Lives, an organization started in the wake of the Parkland Shooting, and a student at Harvard College.

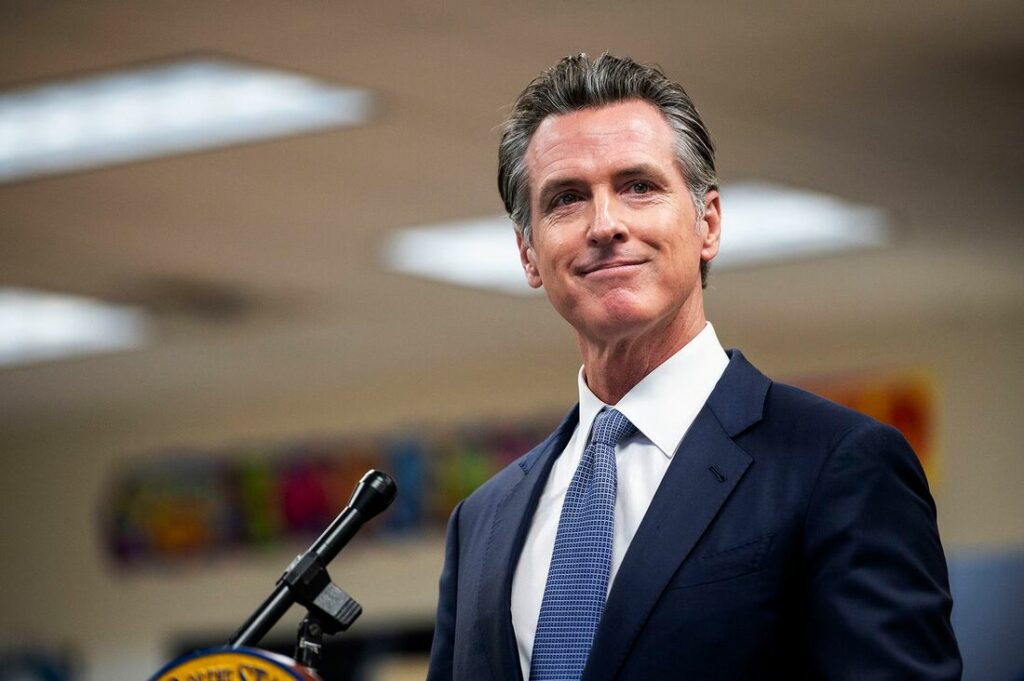

Over the past week, Governor Gavin Newsom of California has broached introducing legislation that would do to gun providers what Texas has done to abortion providers: deputize a massive army of private “bounty hunters” to put them on the defensive. A California initiative would allowany Californian to sue “anyone who manufactures, distributes, or sells an assault weapon or ghost gun kit or parts” and recover unlimited damages. The defendants would have to plead their Second Amendment rights in appealing adverse verdicts — if they could stay in business long enough to do so, which many could not. Governor Kathy Hochul opened the door for a similar approach in New York with earlier legislative action that authorizes suits against gun manufacturers for injuries and deaths linked to firearms.

The decision to borrow this approach — which eliminates the pre-enforcement injunctive remedies that previously shielded federal rights from such assault by ensuring that no state officials amenable to federal suit play a role in the assault on those rights — has drawn handwringing from across the political spectrum. Commentators on the right who only weeks ago championed a similar approach for ending abortion now hypocritically cry foul when the topic turns to saving lives from gunfire. Of more concern, some high-profile liberals and progressives vocally resist such efforts as unprincipled examples of stooping “to the level of conservatives in circumventing federal courts’ authority.”

There is no doubt that Texas’ controversial abortion ban and its injunction-skirting mechanisms represent an alarming affront to federal protection of constitutional rights and to the rule of law. As advocates of such protection, we do not come easily to our endorsement of these efforts. We would much rather follow Michelle Obama’s once timely mantra, “When they go low, we go high.” But doing so here would dramatically misread the moment.

Read the story on Boston Globe