Progressive lawyers start pro bono firm to defend democracy

Say It Louder

Last year, Mark F. Pomerantz and Carey R. Dunne were leading the Manhattan district attorney’s investigation into Donald J. Trump’s business practices.

Now, they have turned their attention to a broader phenomenon that they say the former president represents: threats to democracy in the United States.

Mr. Pomerantz and Mr. Dunne, who resigned last year when the district attorney decided not to seek an indictment of Mr. Trump, said they have formed a pro bono law firm that aims to stem the tide of anti-democratic policies proliferating around the country. The firm — the Free and Fair Litigation Group, which opens its doors this week — is also led by Michele A. Roberts, the former head of the union that represents professional basketball players.

All three founders have extensive experience as litigators, and they plan to defend policies they see as just and bring lawsuits challenging those they believe are undemocratic, the three founding partners said in an interview. Their work will initially focus on voting rights, gun control and free speech.

Read the story on NY Times

The story of the jailhouse lawyer who set dozens free

More of This

Soon after she was sent to Rikers in 2010, Kelly Harnett became a regular at the jail’s law library. She was looking for a loophole, a technical error, something that might set her free.

Harnett was 28 and facing murder charges for the killing of a stranger in a park in Queens. She was innocent, she would tell anyone who would listen; she had been a bystander, unable to stop her abusive boyfriend from choking the man.

Harnett paged through the law books. At first, nothing made any sense. But she decided that if she could simply memorize the statutes, she would understand them and could maybe even become good at law. “And everyone loves something they’re good at,” she told me.

She filed a motion to dismiss her indictment. She wrote and revised briefs, citations, arguments. On one occasion, Harnett was working under a deadline when flying water bugs hatched in an adjacent storage room and flooded into her cell. A guard refused to move her: “Guess what I did? I sat right on the floor, on top of the bugs but on a tipped-open garbage bag that I double-bagged, and got to work.” The motion was denied, but the story became, in her mind, one of triumph and resilience.

Read the story on NY Magazine

The lawyer working to end the rape exception

Less of This

As a young girl in suburban Michigan, in the nineteen-seventies, Rebecca Kiessling was teased for looking nothing like her adoptive parents. Larry and Gail Wasser were Jews who took the family to temple on the High Holidays, and Kiessling, a fair-haired, blue-eyed child, recalls people asking, “Who’s the little shiksa?” Her only sibling, an adopted older brother, acted out in grade school and later got into trouble with the law. In Kiessling’s memory, Larry would joke that “socially deviant behavior is genetic,” a reference to the 1956 thriller “The Bad Seed,” in which a psychopathic child turns out to be the descendant of a serial killer. Gail sewed matching mother-daughter outfits, but that did little to quell Kiessling’s feeling that she didn’t belong. She likes to recount a story about seeing the musical “Annie” and being transfixed by the song “Maybe,” in which the orphan protagonist dreams of her mother and father. When Kiessling and I first met, last spring, she recited some of the lyrics for me. “Betcha they’re good / Why shouldn’t they be?” Annie sings. “Their one mistake / Was giving up me.”

Read the story on New Yorker

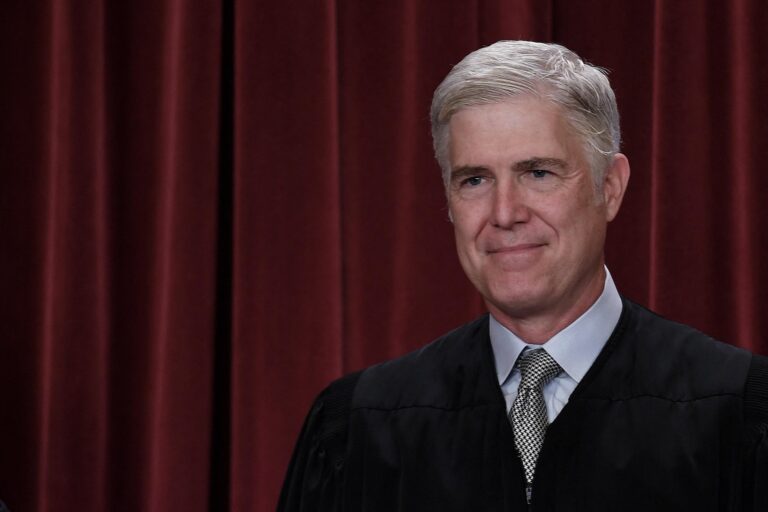

SCOTUS is coming after the right to strike

Speaking Of...

Remember those pesky analogy questions on the SAT? Here’s one for you, straight from Tuesday’s U.S. Supreme Court oral argument:

- When concrete workers went on strike, they returned their trucks to the company yard and left them running, to prevent the concrete from becoming unusable and to avoid damaging the vehicles. Because of these precautions, the trucks were fine, but since the workers weren’t there to deliver the concrete, some of it couldn’t be used.

- Is this scenario more like a) cheese workers going on strike, and some cheese being partly ruined? Or b) security guards going on on strike, leaving federal buildings and employees unattended in the middle of a terrorist threat?

This (not very difficult) question is at the heart of Glacier Northwest, Inc. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters Local Union 174. The dispute is about whether employers can sue unions for economic harm, including that caused by loss of perishable products, that results from workers going on strike.

Read the story on Slate

Apply for Funding from ChangeLawyers

Legal Empowerment Fund